I sped downward through the blue vistas that had flanked America's first frontier, and wondered about the route through the pass that had given the town of Big Stone Gap, Va., its name. Over a long summer weekend, driving a loop off Interstate 81 and taking day hikes, I found the excellence of its roads to be one of many mismatches between Appalachian legend and reality. The traditional image of Appalachia was fixed in the American mind late in the 19th century largely by one man, John Fox Jr., who lived in Big Stone Gap. Fox came to the mountains in the 1880's as a Harvard graduate, when his affluent family from Kentucky's bluegrass country began to speculate in coal and timber. Big Stone Gap was expected to become the Pittsburgh of the south. It didn't, and instead Fox began to write about the mountaineers he met. ''The Little Shepherd of Kingdom Come,'' published in 1903, was the first American novel to sell a million copies, but it was ''The Trail of the Lonesome Pine'' that established Fox's enduring fame and became the basis for an outdoor musical that has been performed for 30 years. In the play, a mining engineer comes into the mountains, meets a beautiful young girl, oversees her education and marries her. Magnificent Appalachian hardwoods fed a lumbering boom around 1900 that took almost all of the great old trees. Breaks Interstate Park, on the Virginia-Kentucky border, offers a rare opportunity to see a remnant of the original forest. Much of the park's timber was floated down the Russell Fork to market, but rugged terrain protected a small area from loggers. I checked into the Gateway to the Breaks Motel, about two miles from the Breaks, on a rainy Friday night the next morning, I drove U.S. Slowly, I hiked three miles on Prospector's Trail from Tower Tunnel Overlook and back by Overlook Trail. Five miles long and averaging 1,000 feet deep, it is called the Grand Canyon of the South.īoth trails overlook a ravine cut through Pine Mountain by the Russell Fork of the Big Sandy River. A railroad was built through the gorge for coal in 1915, and its presence derailed a 1930's effort to designate the Breaks as a national park. By then, the Government was buying cut-over mountains to restore as national forests. It was the middle of July, and overarching thickets of rosebay rhododendron still offered a few white blooms tinged with deep red. Massive trees stood so tall I could hardly make out the silhouette of their leaves above. The trail followed along the base of cliffs in whose fractures grew a great variety of plants. I could hear the tinkling of a tiny creek, but could hardly find it beneath the gnarly roots tangled among the rocks. I saw few people until I emerged near the picnic area around lunch time.

The Breaks was a favorite destination for local people long before it became a park, and I could tell by the balloons tied to picnic tables that several families were having birthday parties. In addition to picnic pavilions, facilities scattered around the park include a motel, restaurant, cottages, campgrounds, a pool and two lakes with fishing and pedal boat rentals. There were plenty of people - the park motel was booked up - but few of them used the trails. IN the more modest residential section below Poplar Hill is the Fox house, a low-ceilinged cabin of cedar shakes and bead board that started with four rooms and ended with 22.

Fox traveled widely as a correspondent for Harper's and Scribner's magazines.

The house, open to the public, is filled with statues, brass candlesticks and fancy bookends.įox married a Viennese opera singer who sang scales on the screened porch off their bedroom upstairs. He died there of pneumonia in 1919, at the age of 56.

Fox was a small, suave man of frail health and weak eyes, vigorous in his youth but later enjoying the luxuries his wealth brought.

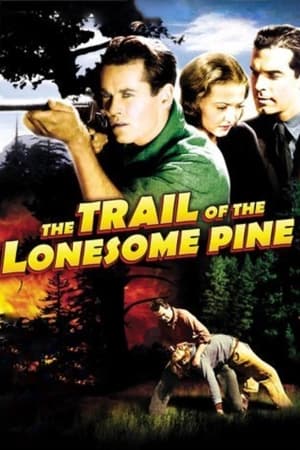

THE TRAIL OF THE LONESOME PINE 1915 CODE

The trail of the lonesome pine june age code#įascinated by mountaineers, he chose to live among them, as does the fictional mining engineer of ''The Trail of the Lonesome Pine.'' Published in 1908, the book had what a review in The New York Times called ''a new sense of reality and a winning charm.'' It covers all the Appalachian archetypes: clans, feuds, moonshine, hostility to strangers and a rough code of honor.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)